The changes which took place within the management of Behrens & Marshall in 1920 clearly decided the direction in which the firm was to develop in the future. It was to continue as a motor company, and agencies unrelated to that development could be handled by the Behrens-Thiem company. Johnnie Behrens himself had retired from the firm in August 1920, and with him disappeared any temptation to deviate from this course.

To the general public the change must have appeared as one in name only. The newly-named Maughan-Thiem Motor Company continued to advertise itself as a Ford Accessory House and to promote the items it offered to Ford owners. It similarly continued to advertise the other lines of more universal application such as A-Pache selfvulcanising patches, Effecto auto finishes, Shafer self-aligning front wheel roller bearings, and so forth. To be sure, some of the earlier Behrens & Marshall agencies were disappearing from the books, including Enfield and Enger cars and Sterling and Redden trucks; but the important Ford sub-dealership remained in the hands of the company and some new highly successful agencies were added. It was the same course but full steam ahead.

News items publicising the fact that Behrens & Marshall had been superseded by the Maughan-Thiem Motor Company added the comment that this business was now essentially a Ford service and sales organisation. By and large this was true; but even as Behrens & Marshall had coupled its Ford activities with the handling of other profitable agencies so too did the Maughan-Thiem company.

Within the first few years of operations under its new name the company gained a package of agencies. Some of these were relatively short-lived, but others proved to be enduring and profitable.

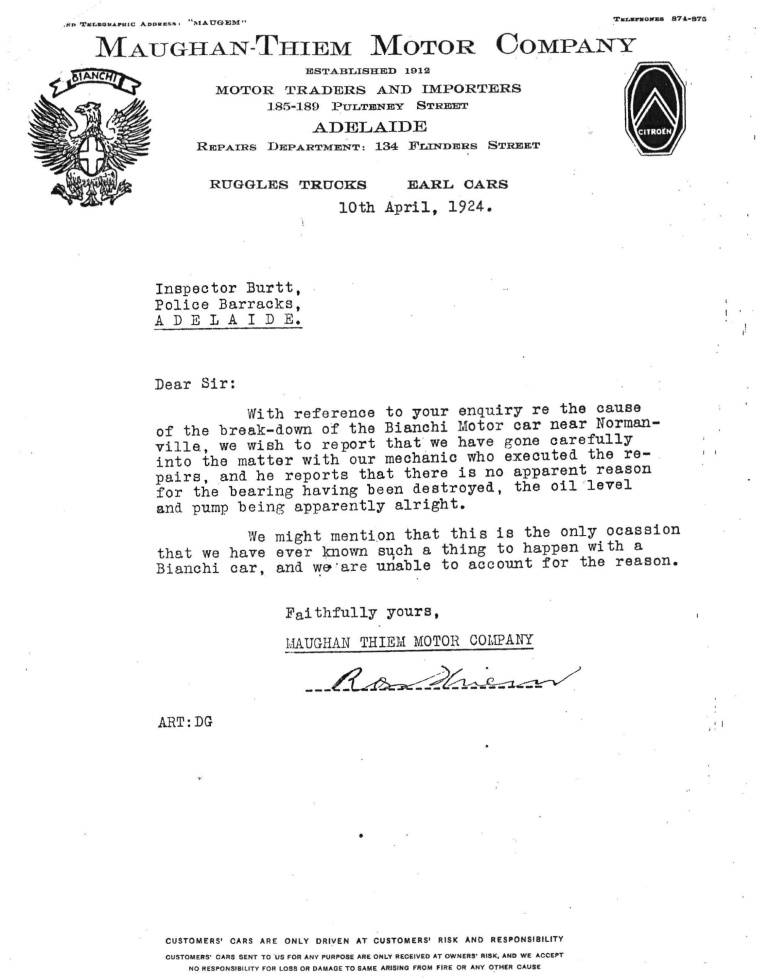

The first of these new agencies was for the Italian Bianchi car, a sturdy 12.1 horsepower 4-cylinder vehicle which cost roughly twice as much as the Model T Ford. The press announcement that Maughan-Thiem company had been appointed local agent for the Bianchi appeared at the end of April 1921, and by the end of the following August the first shipment of chassis arrived in Adelaide, followed shortly by a second. By October the company reported excellent business in Bianchi cars. Both shipments had been sold, and further supplies were on the water. Until about 1925 Maughan-Thiem had good reason for satisfaction with the Bianchi agency, and indeed until the middle of 1923 it was the company’s best seller. After that its importance dwindled, and from about the end of 1925 there is no further reference to it in the company’s books.

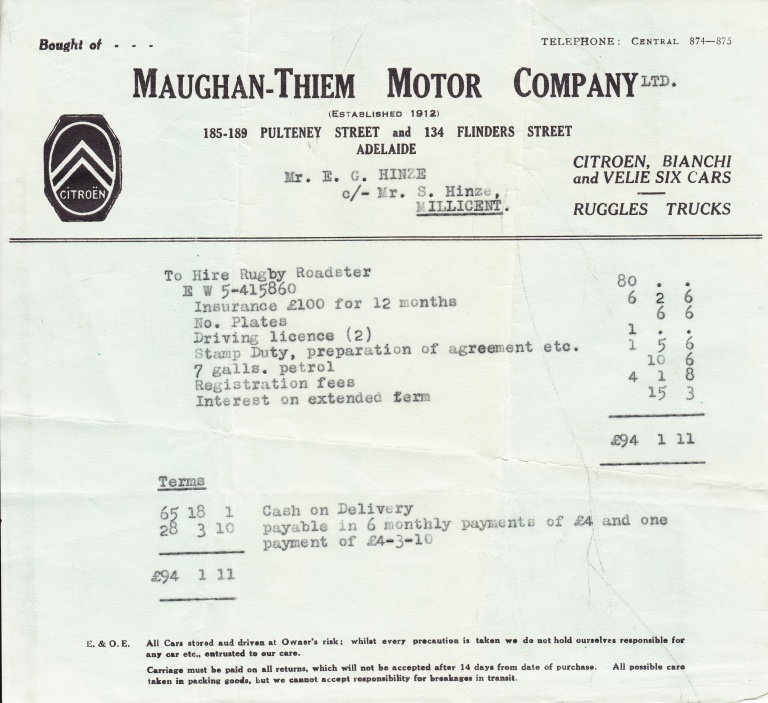

Close on the heels of the Bianchi agency came that for another continental car. In April 1922, just one year after securing the Bianchi agency, it was announced that the Maughan-Thiem company had obtained the agency for the French Citroen car which was previously handled in South Australia by the Moncrieff Engineering Co Ltd. The Citroen had already made a name for itself before coming to South Australia, and for some seven years Maughan-Thiem flourished in its dealership for this popular make of car. Indeed a Citroen car club was formed, and on Sunday 16 September 1923 what the press called ‘rather a unique event in the motoring world’ took place. A fleet of 40 Citroens left the Maughan-Thiem premises for Belair, where prizes were offered in an interesting range of events. These included the first car to arrive at Belair, the most attractive car, the best-kept car, the dirtiest car, the car which had travelled most miles, a skilful driving event for ladies, and an event in which mechanical troubles had to be righted. There was also the usual round of picnic events such as threading the needle, a flag race, and an obstacle race. This was the beginning of a number of such outings which served to emphasise the popularity of the Citroen. The two most favoured models were the larger car, originally a 10 horsepower car which was increased to 11.4 horsepower in about 1926, and the Baby Citroen which was originally a 5 horsepower model and became 7.5 horsepower later on. The Maughan-Thiem company found the Baby Citroen a particularly popular car. It has been described by one who knew it as a sort of cousin to the Volkswagen, a rugged little car about the same size as the later German car with disc wheels. In the 1920s a Baby Citroen was driven all around Australia by a team of trial drivers which included Bill Forrest of Maughan-Thiem, no mean feat for a small car in those days. The Citroen remained on Maughan-Thiem’s books until 1929 and for some years was an important agency for the company. In September 1929 the South Australian agency was taken over by Crawford-Richards Limited of Currie Street.

Three months after securing the Citroen agency Maughan-Thiem added yet another overseas car to its business. In 1916 the motoring editor of The Mail had commented on the performance of the Stutz car in American racing events and had expressed surprise that there was no South Australian agency. Some six years later, in July 1922, the agency for the American Stutz was taken up by Maughan-Thiem, and in September 1922 the first car arrived in Adelaide and was exhibited by Maughan-Thiem at the spring show. The Stutz was an expensive 30.6 horsepower 4-cylinder car, priced at about £1,000 when the Bianchi was about £650. In 1923 a new 6-cylinder model appeared. Perhaps it was too expensive to be popular in Adelaide.

It is thought that MaughanThiem sold one Stutz, but neither the motoring pages of The Mail nor Maughan-Thiem’s books refer to the company selling any, although for a short time the company’s books had the miscellaneous line ‘Other Car Sales’ which may have accounted for one or two Stutz sales.

As with the Stutz, the company’s next agency made only a brief and very modest appearance. By August 1922 Maughan-Thiem was handling the Corbitt truck. A few were sold, but by 1923 this agency had disappeared from the company’s books.

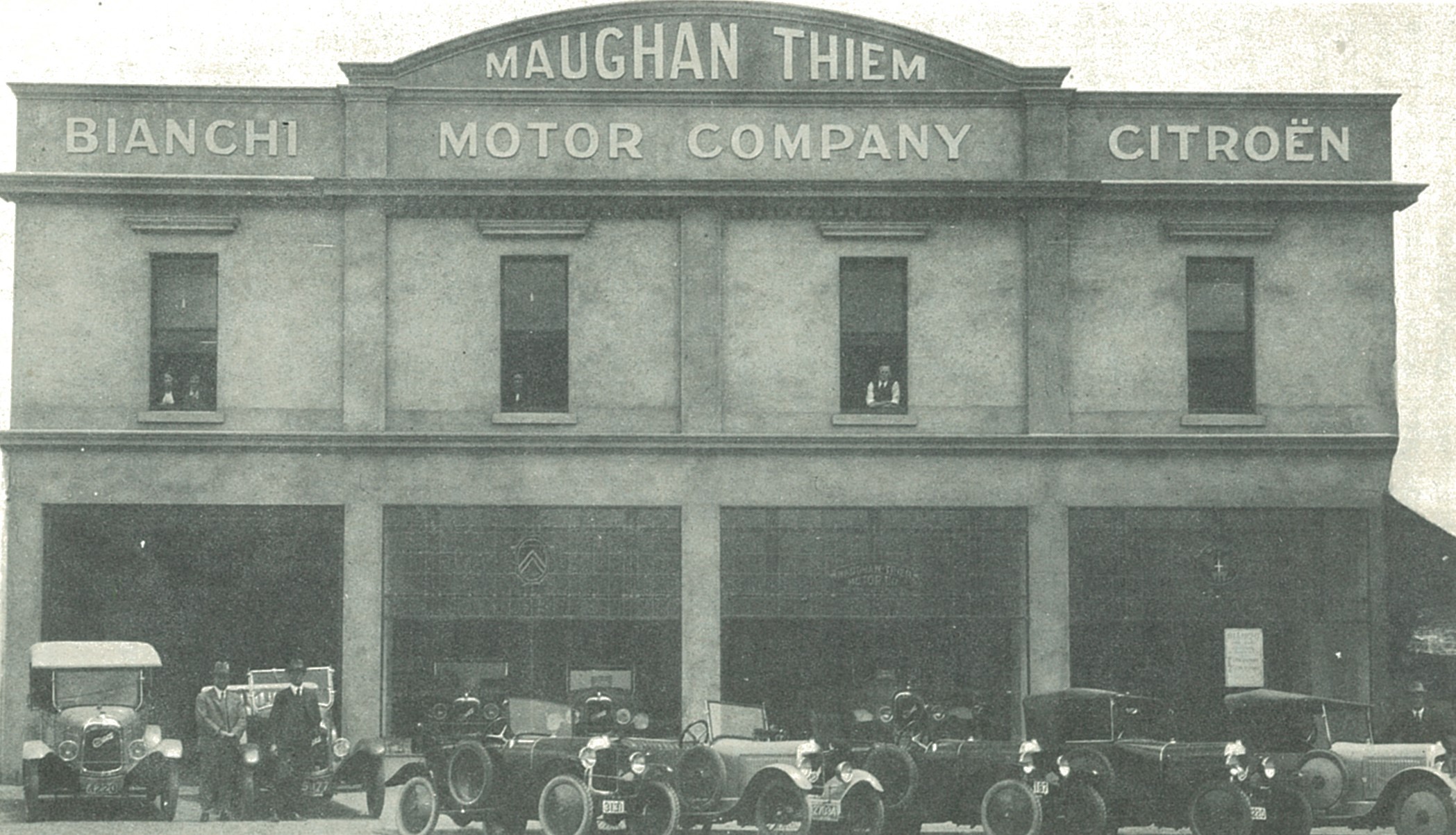

In its Behrens & Marshall days the Flinders Street premises, even after extensions, had become too cramped for the firm’s expanding business. Maughan-Thiem’s new agencies made it imperative yet again that further premises be found, doubly so because even more agencies were being explored. Fortune favoured the company’s search for additional space. The Collegiate School of St Peter, from whom the Flinders Street premises were rented, also had property available around the corner in Pulteney Street immediately north of the Somerset Hotel. It had a frontage of 60 feet on Pulteney Street and a depth of 100 feet, the rear portion of which adjoined the Flinders Street property. In February 1923 the College granted a lease to the Maughan-Thiem company and it was made known through the press that, owing to the rapid expansion of its business, the Maughan-Thiem Company would make a start in March with the building of modern showrooms and a garage on this land adjoining its present property. The building took some months to complete, and it was not until July 1923 that the company was able to announce that it would shortly open bigger premises at 185 to 189 Pulteney Street, where a full range of its agencies would be displayed. By the beginning of November 1923 company advertisements carried the address 185-195 Pulteney Street, which was shortly afterwards altered to the correct address 185-189 Pulteney Street. This address became that of the company’s registered office.

For the time being the projected property expansion seemed sufficient to cope with further ventures and in May 1923, three months after securing the Pulteney Street lot, Maughan-Thiem landed the agency for the American Ruggles truck. For the company this became a lucrative line of business and attracted a brisk trade. On one occasion Ross Thiem drove a Ruggles on a promotion tour across the countryside with a Baby Citroen on the back of the truck to contrast their size. Produced by the Ruggles Motor Truck Company of Saginaw, Michigan, the Ruggles came out in several models. In earlier days they ranged from the three-quarter ton ‘Go-Getter’ to a two-and-a-half ton model. Later no less than fourteen models were advertised, from one to five tons and including a dump truck for road-building and sandcarting and single and doubledecker buses. Mr Mick Tough recalls that Maughan-Thiem handled the first Ruggles double-decker bus, the body of which was built by John Dawson for whom Bruce Thiem had worked for a time. This was used on the Port Adelaide run by the Kent bus line. The company also sold a few single-decker buses and, especially when the Shell building was under construction in North Terrace, some of the dump trucks. Mr Hugh Payne, who used to drive them in from the assembly site at Beverley, remembers that the Ruggles engine was apt to backfire when the starting handle was used, and it became notorious for breaking the wrist of the unwary. The solid rubber wheels were also a hazard on wet tramlines, and on one occasion Hugh Payne found his Ruggles out of control on the wet tramline in North Terrace and in hot pursuit of a hapless policeman on point duty.

Such incidents apparently did not deter buyers, and Maughan-Thiem did well with Ruggles for some ten years.

The Maughan-Thiem Motor Company had come a long way since its early Behrens & Marshall days, when a small staff had attended to the mechanical needs of the Model T Ford. It had taken up profitable agencies for overseas vehicles which the company imported in its own right and not as sub-dealers for another local distributor. Each year profits climbed in a pleasing manner and future possibilities seemed boundless. It is evident that the partners gave serious thought to the form that future might take. In early days the firm had cheerfully associated itself with the ‘Tin Lizzie’ Ford image; Ford jokes drew attention to the car and helped to promote sales. There was still no point in losing the profitable Ford business, but nevertheless the firm had outlived its ‘Tin Lizzie’ days and sought some way to shed that image. The solution seemed simple, perhaps suggested by the example of the Ford distributors Duncan & Fraser themselves.

Like Maughan-Thiem, Duncan & Fraser had linked its Ford dealership with the handling of other makes of car, and in 1920 it had set up a subsidiary firm, Duncan Motors Limited, which concerned itself exclusively with selling the Ford. The subsidiary firm was closely associated with the parent company and operated from its Franklin Street premises.

The Maughan-Thiem company decided to take a similar course. In October 1922 it announced in the press that it had transferred its Ford car sub-agency to the Henry Car Company, the address of which was the Maughan-Thiem premises at 134 Flinders Street. The Henry Car Company flourished for about eight months. The motoring columnist of The Mail reported its Ford sales, at first under the heading ‘MaughanThiem Motor Company’ and then later as a separate item under the Henry heading; and by the end of 1922 the new subsidiary company had sold over one hundred Ford vehicles. For a short time the partners obviously held high hopes for its future. When in February 1923 MaughanThiem announced its intention to build a showroom and garage in Pulteney Street it added that the Flinders Street premises would be used exclusively by the Henry Car Company for the distribution of Ford vehicles and as a Ford service station. This intention, however, was not completely realised. Pulteney Street was not ready for use until November 1923, and Henry Car Company news items and advertisements stopped in the previous June. For about six months after June 1923 Maughan-Thiem in its own name resumed its Ford sub-dealership, and towards the end of October advertised the Flinders Street premises as the Maughan-Thiem Motor Company Ford Service Station where Ford cars and trucks could be bought; but by the end of 1923 Maughan-Thiem had ended its Ford sub-dealership. When the Henry company was set up a complete break with Ford was obviously not intended. The reason for this eventual break can only be guessed in the absence of company records; perhaps it is significant that in June 1923, when the Henry company disappeared, George Mason of Kent Terrace Norwood was given a Ford sub-agency for Adelaide. George Mason, like Johnnie Behrens and Ross Thiem, had spent years with Duncan & Fraser and with its Ford subsidiary Duncan Motors. Since Maughan-Thiem was successfully promoting other agencies it was perhaps seen fitting that the Ford mantle should fall on Mason’s shoulders. At all events, it was not until 1958 that the association between Maughan-Thiem and Ford was resumed.

Meanwhile other agencies came and went. In May 1923, the month in which the Ruggles truck agency was taken up, Maughan-Thiem became agent for the Earl car which had previously been distributed in South Australia by Vulcanisers Limited. The Earl was described as a combination of beauty and utility, with low racy lines and luxurious seating. But, like the Stutz and the Corbitt, the Earl created scarcely a ripple on the surface of Maughan-Thiem’s growing pond. It was basically the same as the Briscoe, which it superseded; but Earl Motors Incorporated of Michigan was only in production for two years and in all only about 2,000 cars left the factory. Maughan-Thiem took the agency about the time production ceased, and the company sold only a few Earl cars.

In July 1925, after the Earl agency had vanished from its books, Maughan-Thiem sold one lone Earl.

A year after the Earl agency came that for another American car. The Velie Corporation had been in production since 1908 or 1909, and for a time Murray Aunger had the South Australian agency. When MaughanThiem took it in April 1924 Velie had just commenced production of the new Velie Six range of cars. The first shipment arrived in August 1924, and the 50 horsepower overhead-valve aeroplane-type engine created much interest. In June 1925 a cut-away working engine was in operation in the Maughan-Thiem showrooms with every working part visible and lit up at night. Press items and Maughan-Thiem’s books show that the Velie, priced at about £500, sold well for a time and in particular in 1925 and early 1926. Nevertheless this agency, like the Earl, did not last long. The Velie Corporation ceased production in 1928, and Maughan-Thiem made no further sales after mid-1927.

Continue Reading

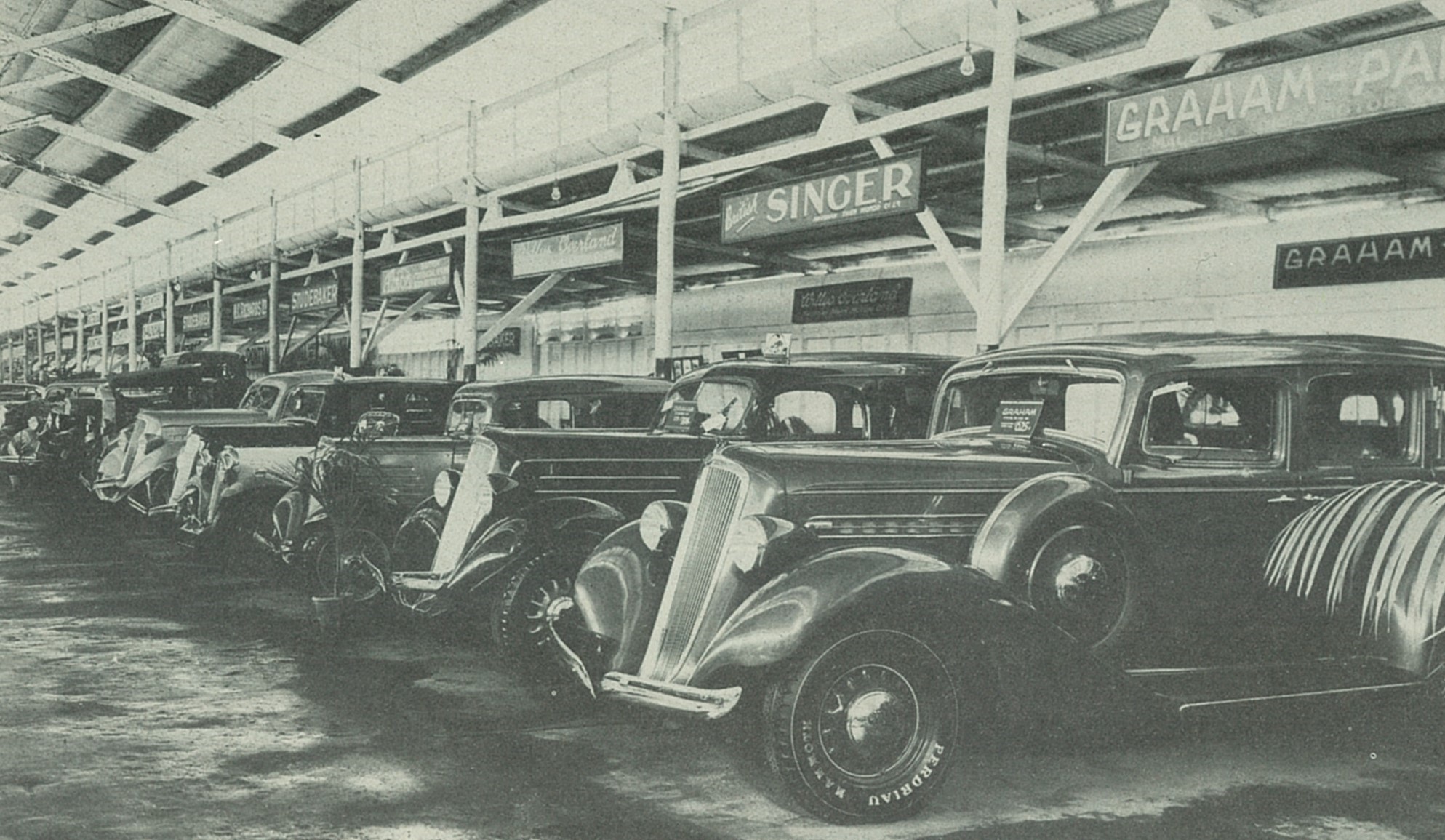

Once again, as agencies accumulated, the old chronic problem of floorspace emerged. The new showrooms at 185-9 Pulteney Street were scarcely opened before their limitations were felt. The Bianchi, Ruggles and Velie were selling well, and in the Citroen Maughan-Thiem had a best-seller. Citroen sales for November 1925 topped the State’s list of registrations, and in the first five days of the following month forty vehicles were sold. Customers in December 1925 were offered ten body styles from which to choose, and even children were catered for with a toy model selling for seventeen shillings and sixpence. In May 1924 it was reported in the press that, owing to increased business, the company was in the process of enlarging its Pulteney Street premises to accommodate a special department to assemble and demonstrate the Ruggles truck. The alterations, it was said, would increase the company’s premises to 20,675 square feet. Apparently this too proved insufficient, for a year later it was again announced that, due to the increased demand for the various lines handled by the company, the showroom space would be doubled for the display of the full range of Citroen, Velie and Bianchi cars and Ruggles trucks.

In retrospect these years of prosperous expansion in the mid-1920s can be seen as the calm before the storm. Some writers see the years 1925 to 1928 as the prelude to the Australian depression, as a period of stagnation with a fall in production and in per capita consumption of goods and services. The collapse of the Wall Street stock market late in October 1929 is generally seen as the final straw which broke the back of the Australian economy and introduced depression on a full scale. For a number of reasons the full severity of the depression hit South Australia at least two years before that date. The state government had over-spent in an effort to develop utilities such as roads and railways, and a heavy interest bill resulted. To meet what had become a financial crisis nearly all state taxes and charges were increased in 1927: railway fares and freights, water and sewerage rates, wharf charges, hospital fees, taxation, and the rest.

From June 1927 unemployment became a serious problem as public works were retrenched; and to make matters worse, 1927 saw the beginning of a three-year drought and rural depression.

By the middle of 1927 the effects on the motor trade were beginning to appear in the State’s monthly statistics for the registration of new motor vehicles. In July 1927 there was a slight drop, and this became more pronounced in the following months. By the end of 1927 newspapers were commenting on the slump. The Mail pointed out that November was the worst month for the motor trade that year, and blamed the drop in car sales on what it was already calling ‘the all-round trade depression.’ New registrations in January 1928 were the lowest January figures since 1923, and the figures for later months in 1928 continued to show the effects of depression: 807 new vehicles registered in January 1928 as against 1,399 in January 1927, 711 in February 1928 as against 1,330 in February 1927, 798 in March 1928 as against 1,323 in March 1927, and so on. There was a slight improvement in November and December 1928 and January 1929, and it appeared that the worst might be over. However, the figures from February 1929 showed that such hopes were illusory; and worse followed. In 1930 new registrations totalled 3,214 as against 7,239 in 1929. The figures for 1931 were disastrous. Only 698 new vehicles were registered in that year. The recovery in new motor sales set in very gradually in 1932, when 1,019 new registrations were recorded, and 1933 was a little better with 1,723. It took a few more years for the new vehicle business to get fully back on its feet. In the meantime the problem was exacerbated by the fact that in many cases those who already had cars locked them up and did not renew the registration, to the detriment of State finance. In September 1931 the consequent loss of revenue to the State government was put at £50,000 Until the height of the depression South Australia had been the most motorised State in the Commonwealth. In 1929 there was one vehicle for each 7.8 of population, but by 1931 this had slipped back to one for each 8.7 and South Australia dropped to second place behind Western Australia.

The only slight consolation for motor traders during these years was the used car business. Newspaper columns reflected this change. In 1931 the greatly reduced motoring section of The Mail, for example, was often given over to guidance in the selection of second-hand vehicles and in the care and maintenance of old cars. There was hardly any point in continuing to report on new vehicles when figures showed that in that year Adelaide dealers sold six times as many second-hand vehicles as they did new ones. Those who had used cars to sell were even able to find ready customers and demand sometimes exceeded the available supply.

These were hard years for the Maughan-Thiem company, as its profit and loss accounts demonstrate. Until the period ended 31 March 1926 business was good and returned sound profits. In the following six months, ending 30 September 1926, a loss of £1,340 appeared in the books. The next six months to 31 March 1927 provided a slight respite with a profit of £957, but thereafter the books show an annual loss until the year ended 30 June 1935, when a small profit of £510 was recorded. The firm had to survive eight lean and profitless years. Sometimes it was unwillingly compelled to increase the hardships of its customers, many of whom could not keep up their payments on vehicles bought on terms and consequently had them repossessed. Maughan-Thiem was obliged to repossess a number of Ruggles trucks, for example, and stored them at Ross Thiem’s Sunnyside property. To offset some of the resultant loss the firm for a while took a carting contract and used some of these Ruggles to carry apples from Balhannah to Port Adelaide.

Needless to say, such measures did little to ameliorate company losses.

It was during the depression period that the firm finally decided to become a private limited company, although the forerunners to this decision extended back into more prosperous times.

By 1923 the partners had permitted the firm’s secretary Mr L.R. Rasch to put money into the firm and earn interest on it. By September 1925 he had deposited £823 in this way. Shortly after that date Rasch left the firm and took his money with him. Perhaps the partners saw Rasch’s example as something worth further exploration, for in 1925 they sought the advice of their auditors Thos. C. Walker & Syme about the possibilities and implications of forming a company and issuing shares. At the time Max Syme, who replied 21 October 1925, was cautious. He obviously knew that Ross Thiem and Fred Maughan were strong-willed men. Whereas, he said, the business was currently their own and they were responsible only to each other, if they formed a company they would no longer own it and would have to administer it for other people. If he were any judge, Syme added, this would interfere greatly with the privileges they enjoyed at present, since they had been in the habit of doing as they pleased. He also pointed out that when shares were issued to an employee ‘your relations become somewhat different, and where previously it was always possible to dispense with him, it becomes impossible to do so except with his consent.’ To be sure, Syme added a handwritten postscript pointing out that companies had certain things to recommend them; but the apparent dangers which he stressed evidently gave the partners food for thought, and the decision to form a company was delayed. Syme’s advice was also heeded in a further respect. Les Rasch’s successor as secretary, Harold George Burdon, was also permitted to invest money in the firm at the rate of £1 weekly and to share in the profits in proportion to the amount he had invested. However, in an agreement dated 1 July 1926, eight or nine months after Max Syme’s letter, it was specified that this under no circumstances made Burdon a partner nor did it limit the rights of the company to dispense with Burdon’s services at any time it saw fit.

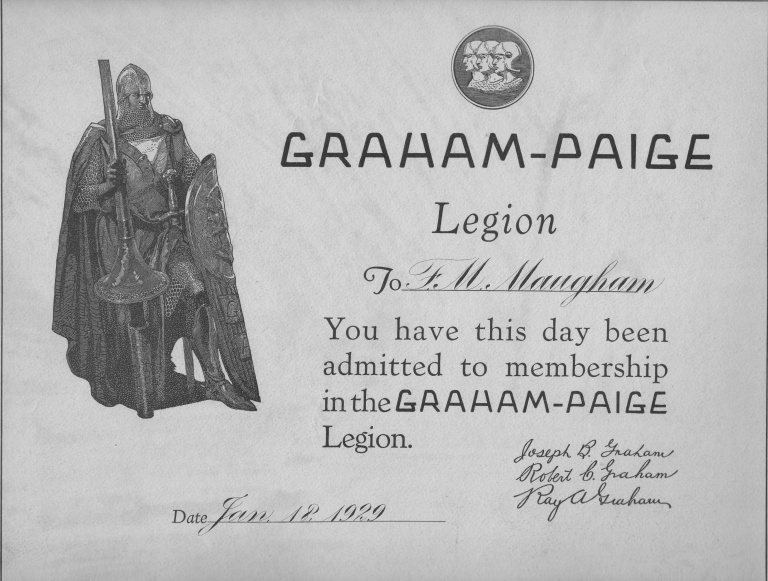

By 1928 the partners had become convinced that there were good reasons to form a limited company. In the six months ended 30 September 1927 the firm recorded a loss of £3,177 and in the following six months to 31 March 1928 a further loss of £3,731. In these depression years the firm had obtained the agency for the American Graham-Paige car. Profit and loss accounts offered little comfort to the partners and an injection of capital was needed to finance the import of this new line of business. On 1 April 1926 Mr Bruce Thiem had been admitted into the firm as a partner. He had married a daughter of John Walker Fox, of the Flinders Street firm of builders and contractors Fox Ey & Thomas. Fox and his partner Ernest George Ey agreed to join a limited company if it were formed, and consequently on 1 August 1928 Maughan Thiem Motor Company Limited was incorporated under The Companies Act 1892 as a limited company. The shareholders at the time of incorporation were F.M. Maughan, A.R. Thiem, B.M Thiem, Mrs G.G. Thiem, and members of the Fox and Ey families. The total capital of the company was increased from the £11,000 represented by the interest of the three partners in the firm to £21,000 in fully-paid £1 shares. The first directors were E.G. Ey (chairman), F.M. Maughan and A.R. Thiem (joint managing directors), B.M. Thiem, and J.W. Fox. H.G. Burdon was secretary although not a director.

The Maughan-Thiem company had never been content to rest on past laurels, and the newly-incorporated company clearly thought that to do so now was hardly the best way to face hard times. It tried to improve its situation by means of another agency to compensate for dwindling Citroen and Ruggles sales.

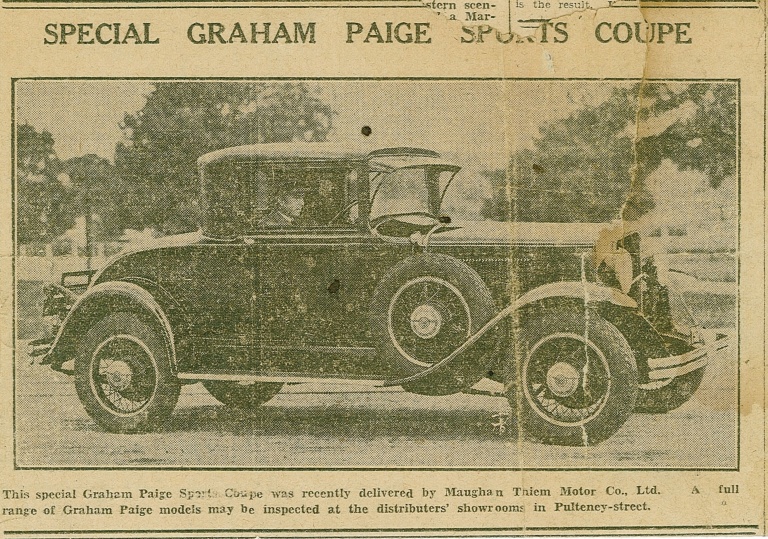

This agency was for the new Graham-Paige car. The three Graham brothers had operated a very successful truck manufacturing business in conjunction with the Dodge brothers, who had supplied the engines. In 1926 they sold their truck business to Dodge and gained control of the Paige Motor Car Company of Detroit. The new Graham-Paige Motors Corporation then set about producing a new range of cars bearing its name. In July 1928 it was made known that the Maughan-Thiem company had secured the agency for South Australia and Broken Hill, and by the end of August the Graham-Paige was on display in the company’s showrooms. It was fitting that the first Graham-Paige delivered in South Australia, a 629 model seven-passenger sedan, was to Mrs E.G. Ey, whose husband was a shareholder and first chairman of directors of the limited company which had been formed to import the Graham-Paige car. This make of car was in all an impressive limousine, and both Fred Maughan and Ross Thiem drove 612 models for a time. Maughan Thiem was the first company to put out a Graham-Paige coupe utility, which had a wooden utility body.

For a year or so it seemed that the Graham-Paige might fill the gap created by the loss of the Citroen and Ruggles agencies. For the two years ended 30 June 1929 and 1930 it was the company’s best line of business, far ahead of its only competitors the ‘general sales’ and ‘repairs’ lines. Then the severity of the depression became apparent. New Graham-Paige cars registered during 1930 totalled 36; in 1931 the number fell to 5, and indeed between March and November 1931 no new Graham-Paige cars were registered. In 1932 the number rose to 11, but even that improvement meant that less than one car was sold each month. In those three years 1930-32 Maughan Thiem sold a total of 52 Graham-Paige cars; and by this time it was the company’s sole agency. Company records show that 1933 to 1935 were even worse years, although by then other new agencies were beginning to yield more promising results. Sales of the Graham-Paige, renamed Graham from 1934, improved slightly from 1936, but by the end of 1938 this car dropped out of the company’s books.

Maughan Thiem survived these disastrous times despite eight years of steady losses. The following table, compiled from company profit and loss accounts, shows the effects on the more important lines of business.

| Year Ended | New Vehicle Sales (£) | Used Vehicle Sales (£) | Repairs (£) | General Sales (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 September 1927 | 13,595 | 263 | 1,732 | 2,148 |

| 31 March 1928 (Six Months) | 2,368 | – | 833 | 1,099 |

| 30 June 1929 | 9,975 | – | 1,168 | 1,645 |

| 30 June 1930 | 5,151 | – | 1,654 | 636 |

| 30 June 1931 | 864 | 1,367 | 955 | 452 |

| 30 June 1932 | 639 | 2,805 | 971 | 355 |

| 30 June 1933 | 2,606 | 1,364 | 1,337 | 318 |

| 30 June 1934 | 2,655 | 1,144 | 894 | 267 |

Sales of the Graham-Paige gave to new vehicle sales in 1929 and 1930 some slight semblance of respectability, and by 1933 and 1934 Singer and Willys sales began to affect the figures. In the intervening two years 1931 and 1932 used car sales were the mainstay of the company’s meagre income. The depression had other effects. General sales fell drastically, and income from repairs also declined; and, of course, all aspects of the company’s business were hit most adversely. Some other firms collapsed under the stress of the time, and Maughan Thiem was fortunate to be able to ride the storm.