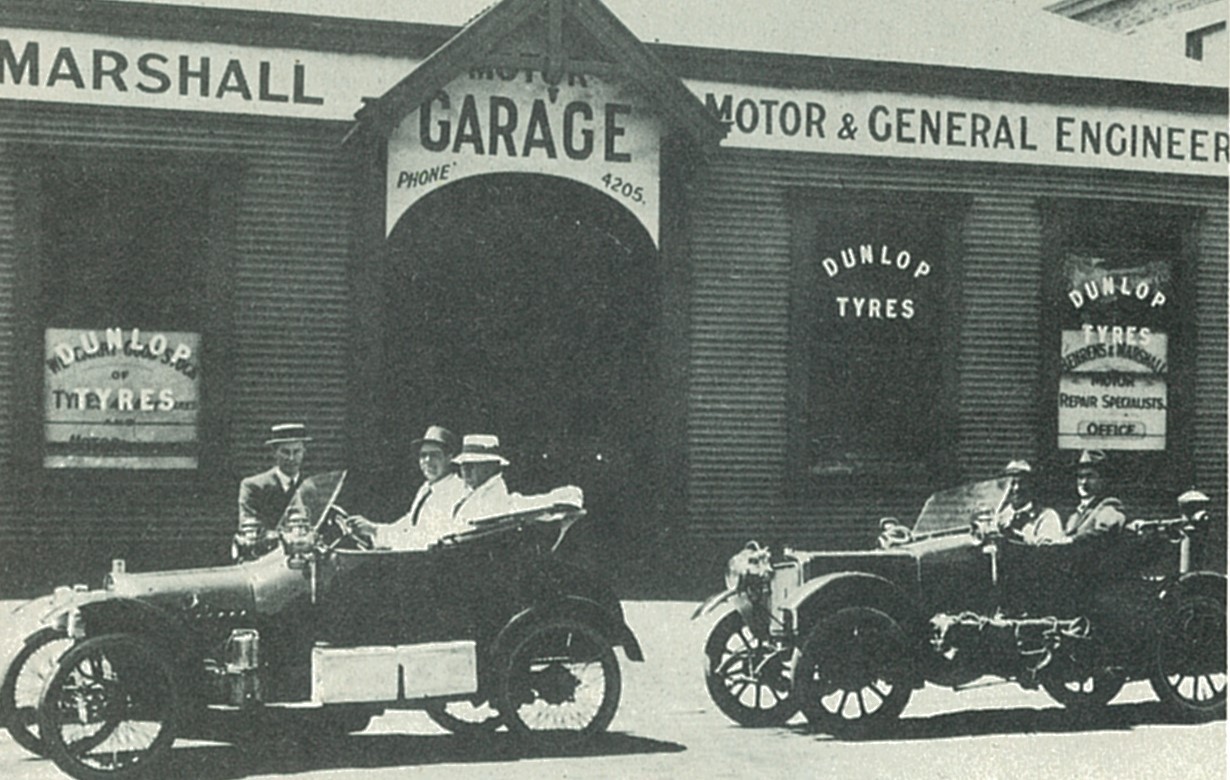

The firm of Behrens & Marshall started its career, according to the articles of partnership dated 2 July 1912, as motor and cycle builders and electricians and importers of motor and electrical goods and appliances. The skills of the two foundation partners were thus included in the official statement of the business of the partnership; Behrens was an engineer, Marshall an electrical engineer. In its first appearance in Sands and McDougall’s South Australian Directory in 1913 the firm was described as motor and general engineers. Before venturing out into more ambitious enterprises the partners started with what they knew they could do well.

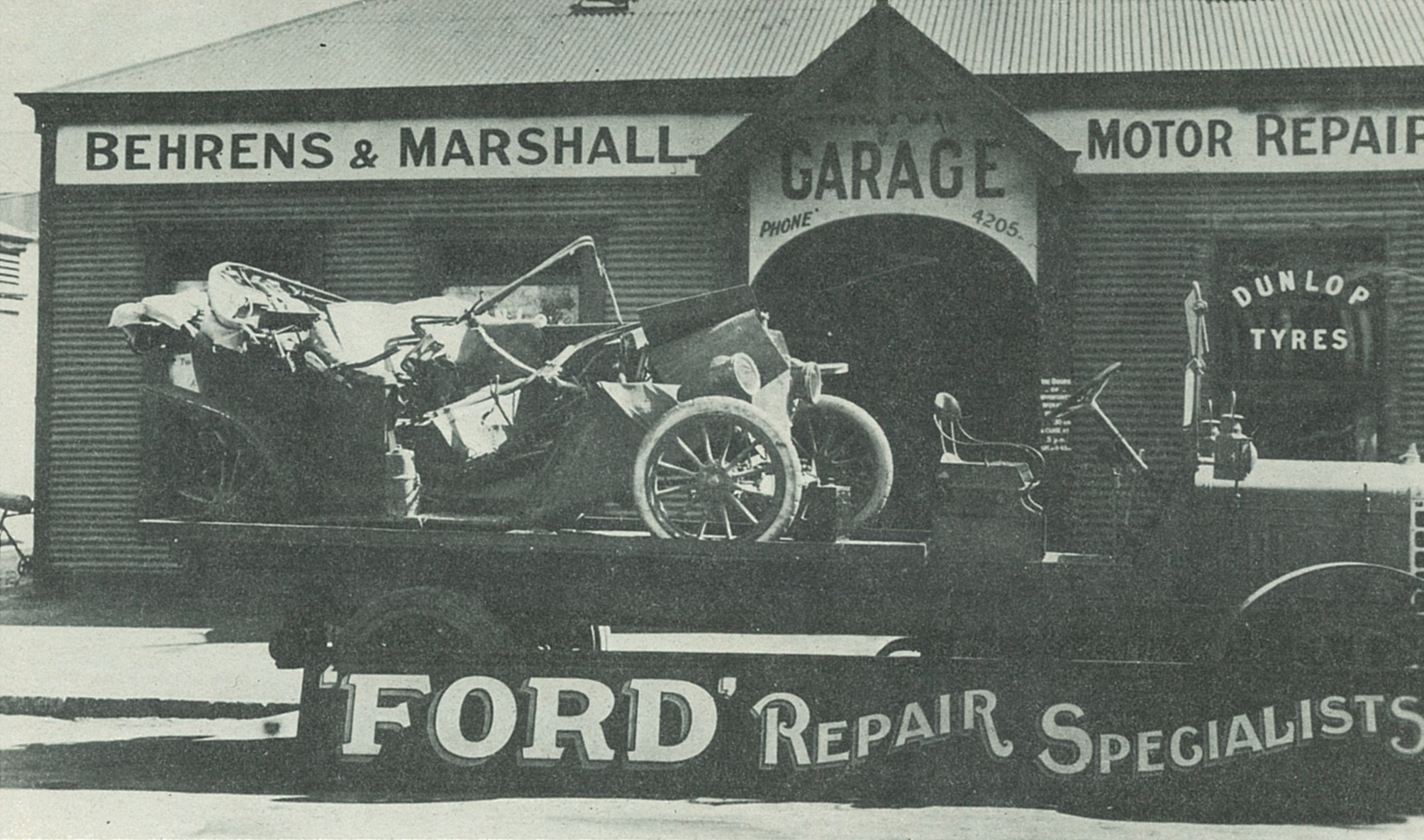

It is therefore no surprise to find in the firm’s first ledger that repair work was the main profit earner during the first six months. Income for the opening half year which ended 31 December 1912 totalled, £1452, and of this repair work accounted for £805 and sales £506. It is recalled that most of the repair work was on Model T Ford cars, for example on the differential. This was apparently prone to trouble, and Behrens & Marshall did a thriving business in repairing it. As with most things, there was a right and a wrong way to put the Ford differential together again. Mr Bert Baldock ruefully remembers the first time he was entrusted with this task. After he had re-assembled it the engine was started and the clutch was let in with the car in forward gear; but the car moved off in reverse. The differential cases had to be changed around to rectify the problem. The Behrens & Marshall mechanics were kept busy with all manner of repair work, and although after the first six months the value of sales exceeded that of repairs this was due to an increase in sales of accessories rather than to a decline in repairs. In 1919, during a visit to Canada, H.A. Behrens went as far as to say that over 75 per cent of the cars owned in South Australia had passed through their garage for attention at some time or another. In fact for a while, during the depression years of the 1930s, income from repairs was second only to that from the sale of used cars and exceeded income from new car sales.

By 1917, and possibly earlier, Behrens & Marshall were also in the business of buying used cars and trucks, putting their engineering skills to work in reconditioning them, and reselling them. From the firm’s records it is clear that some of these were used as shop vehicles before they were sold, and the majority were Fords.

After the opening six months sales took the leading place in the firm’s profit and loss accounts. For the ten months ended 31 October 1913 sales brought in £1658 and repairs £1120, for the twelve months ended 30 April 1916 the figures were £5275 and £1259 respectively, and so forth. From the firm’s various advertisements it is possible to gain an idea of the items it sold. Even as much of the repair work was carried out on the Model T Ford, so too many of the accessories were for the Ford. For example, in February 1916 Behrens & Marshall advertised the ‘ Perfection’ self-starter for the Ford car; they bought their supplies from Cornell Ltd of Pirie Street. Later they advertised another brand of self-starter for the Ford, the ‘Genemotor’, made by the General Electric Company. Later again, in September 1919, they turned to yet another Ford self-starter which was also a lighting system for the vehicle. This was the Heinze-Springfield, apparently a good selling line priced at £38:10:0. Perhaps this was the one Mr Bert Baldock remembers; if so, the lighting was driven from the fly wheel, so that the faster the car was driven the brighter the lights shone, and the slower the pace the dimmer the lights. In April 1916 Behrens & Marshall, now describing themselves as Motor Specialists, advised those wanting to do their own minor Ford repairs economically to buy from them cylinder head wrenches for 2 shillings, valve grinders for 2 shillings, fan belts for 2 shillings, and anti-rattlers for 2 shillings and 6 pence. There were other Ford accessories, such as the Holley manifold which was said to give an increase of 23 to 28 miles per gallon on a half-ton Ford lorry and 14 to 18 miles per gallon on a one-ton Ford truck; the Moore auxiliary transmission for Ford cars and trucks; and the Duntley ignition timer for Ford cars.

Another unusual Ford line which Behrens & Marshall handled was the Redden ‘Truck-Maker’, supplies of which they obtained from the sole South Australian agents Cornell Ltd. The Redden was designed and developed by C.F. Redden and was a kit for converting Ford touring cars into one-ton trucks. The Ford wheels were removed from the back axle and replaced by sprocket wheels with solid rubber tyres. A channel steel truck frame was slipped over the frame of the car and bolted into position, and the whole conversion took only a few hours. The first supply of the Redden truckmaker arrived in Adelaide in October 1916, priced at £130, and Behrens & Marshall continued to sell it until early in 1919. The firm in its advertising claimed to be always first in the field with the latest accessories for the Ford, and it quickly established a reputation in caring for the needs of the Ford owner.

The firm also carried a varied and colourful array of other lines not exclusively designed for the Ford. For example, in March 1916 Behrens & Marshall were advertising No-Jah, ‘the only efficient shock absorber Made in Australia for Australians’ and supplied by Cornell Ltd. In the same year they were sole agents for Castrol oil. There were many other items, such as the self-aligning Shafer roller bearings for front wheels, tyres by Goodrich, Dunlop and Barnet Glass, Essenkay tubes which were advertised as proof against blowouts, Shell benzine, Pyrene fire extinguishers, the Stewart vacuum gasolene tank which was claimed to save 10 to 15 per cent fuel consumption, Edison batteries, and the Stewart mechanical horn which, it was promised, would clear the way.

Continue Reading

In the main, the items which Behrens & Marshall needed for their repairs and sales business were bought locally and from a wide range of suppliers. The firm’s first ledger contains the names of some 90 firms from whom purchases were made between August 1912 and July 1914. But from the beginning the partners’ ambitions extended beyond the retailing of accessories obtained from local wholesalers and the servicing of cars. The 1912 articles of partnership included importing in their business description, and by the end of the first year of business this ambition was realised. The 1914 South Australian Directory included Behrens & Marshall in the list of ‘Cycle and Motor Car Makers, Importers and Agents’.

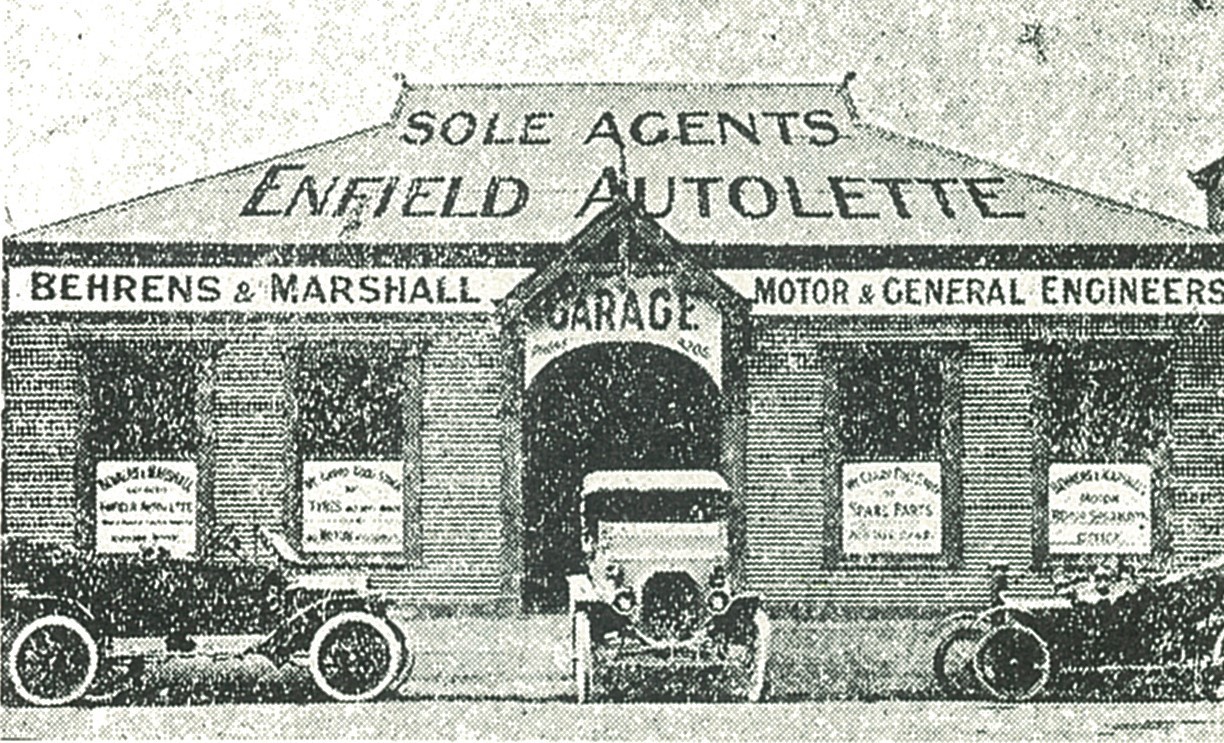

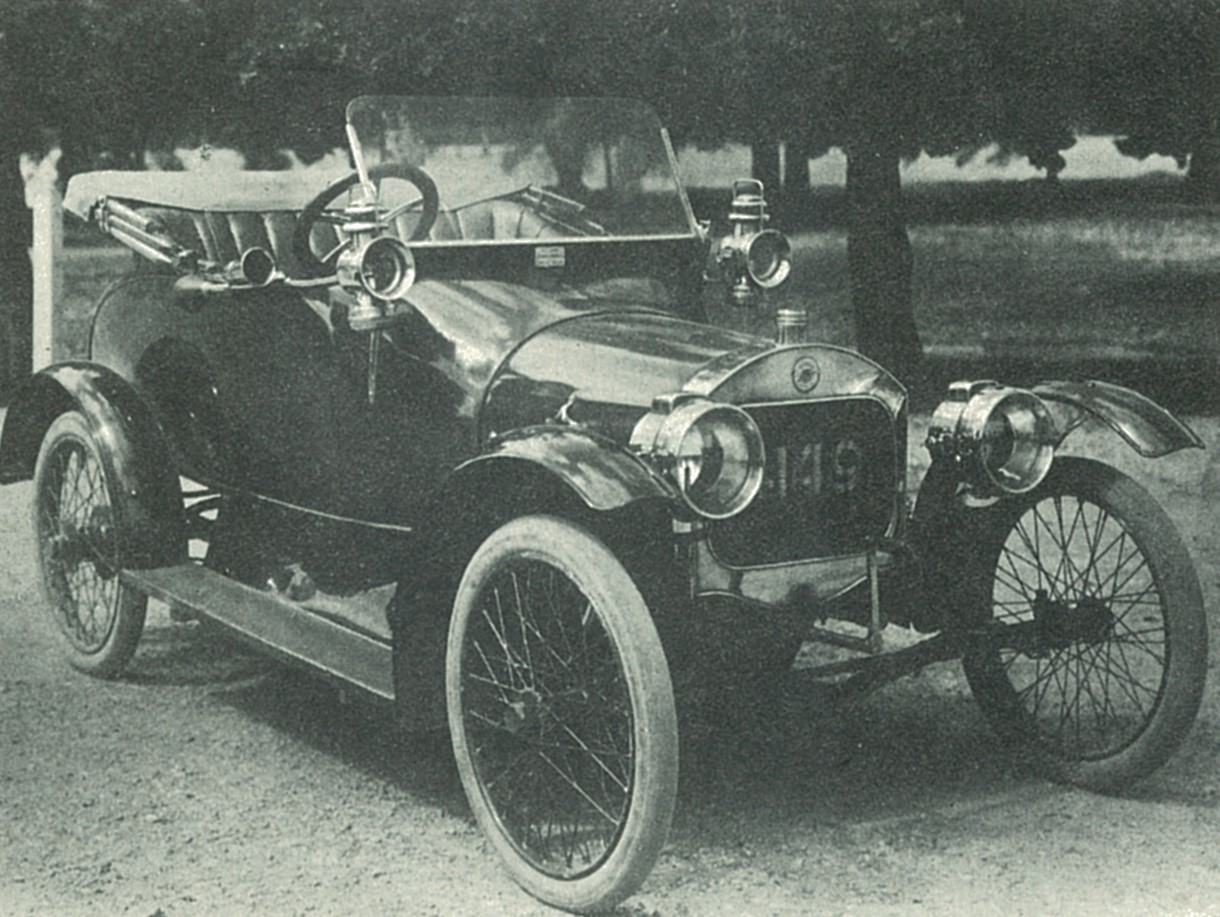

On 30 August 1913 Behrens & Marshall’s first advertisement in The Mail made it known that the firm was agent for the Enfield Autolette, and a small news item in the same issue repeated the information. Officially classed as a cycle car the Enfield Autolette had a body described by the press as a ‘torpedo’ body ‘of the streamline type’. It was powered by an 8-10 horsepower water-cooled motor and did 45 miles to the gallon, had three forward and one reverse gears, and was priced at £200. It was classed as a two-seater, but was wide enough to carry three. This little car quickly attracted favourable attention, and the motoring columnist of one paper reported after a test drive that ‘all that could be heard from the engine was a soft purr.’ By the end of 1913 Behrens & Marshall had sold quite a number and had booked many further orders, and indeed for a while the firm was closely associated with the Enfield. According to a newspaper report Behrens’ wedding on 20 May 1914 was to be a real motorists’ turnout at which the Enfield would take a prominent place, and by 12 June 1915 The Mail had a photograph of the Flinders Street premises with the words ‘Sole Agents Enfield Autolette’ painted across the roof. Just how long the Enfield agency lasted is not known. The same photograph re-appeared in the press in April 1918; but by September 1922, when details of the firm’s various agencies can be extracted from its profit and loss accounts, it is not mentioned.

With the Enfield Autolette the firm commenced a long and successful history of handling motor agencies and franchises. In 1916, perhaps encouraged by this first venture, Behrens & Marshall obtained two more agencies in the one year. Shortly afterwards others followed.

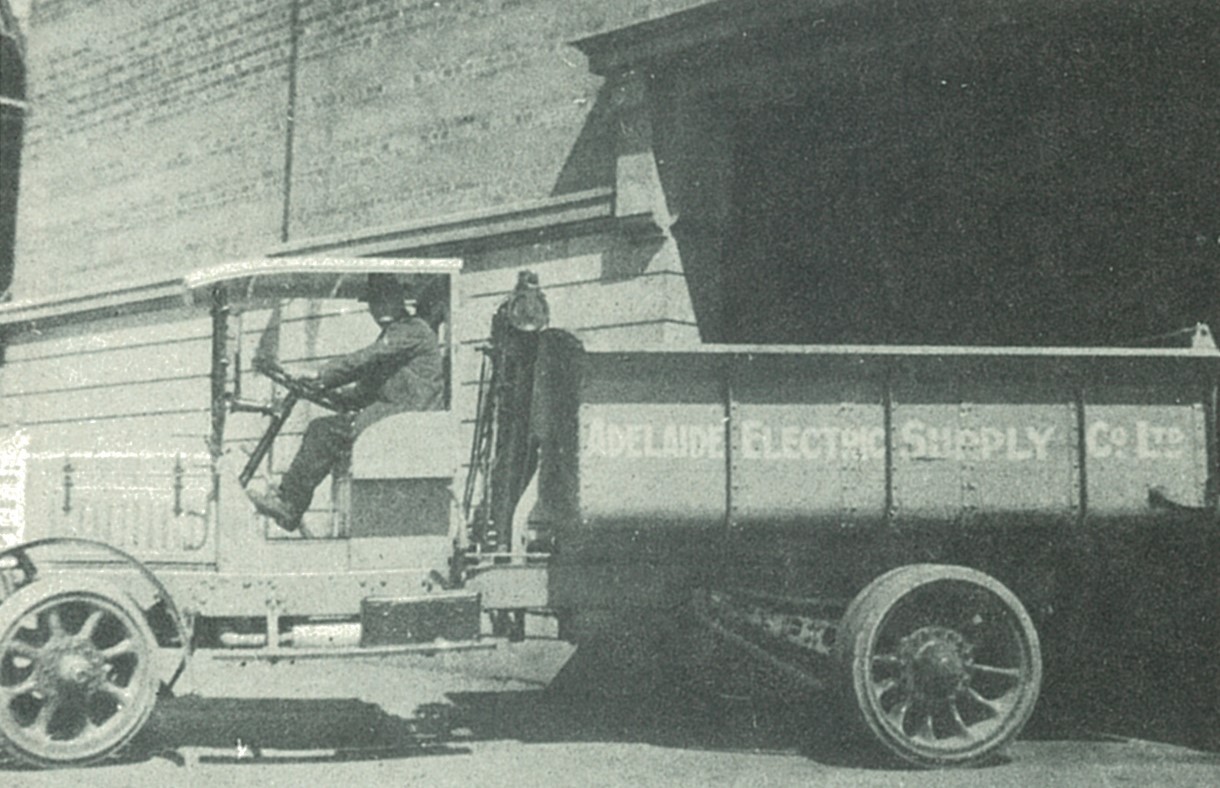

The first was for the Sterling heavy duty truck, which Behrens & Marshall were advertising as sole agents by June 1916. This was advertised as a worm drive chain-driven vehicle with solid wheels, built with the Steel Railway Car Builder’s factor of safety. In 1916 two models were offered; the two-ton truck selling at £775 and the three-and-a-half ton truck at a price of £850. Later, in May 1919, Behrens & Marshall supplied what was reported to be the largest motor in the State and perhaps in Australasia. This was a Starting seven-ton dump truck fitted with a Wood’s patent hydraulic hoist which loaded and unloaded the truck automatically. The vehicle was supplied to the Electric Supply Company to carry coal from Mile End to the city at an automatically governed speed of 15 miles per hour to save wear and tear on the motor. It was fitted with large dual wheels at the back, fourteen inches wide, to carry what was said to be a heavier load than previously carried by any motor vehicle in Australia. Due to delays it apparently took two years for the Sterling Motor Truck Company in Milwaukee to land it in Adelaide. Behrens & Marshall still had the Sterling agency in 1920, but it too had disappeared from the firm’s books by September 1922.

The first car handled by the firm, the Enfield Autolette, was small and relatively cheap; the next was much larger and was an unusual and expensive car. This was the Enger, for which Behrens & Marshall advertised themselves to be sole agents in December 1916. The unusual feature was that it was a twin six which could be run on six cylinders or switched over to twelve. The firm’s advertising made much of this for a while, pointing out that the car had emergency power in abundance but used fuel for this surplus power only when called on to do so. The Enger is not mentioned in the itemised company accounts from September 1922, and press news items give no indication how many were sold.

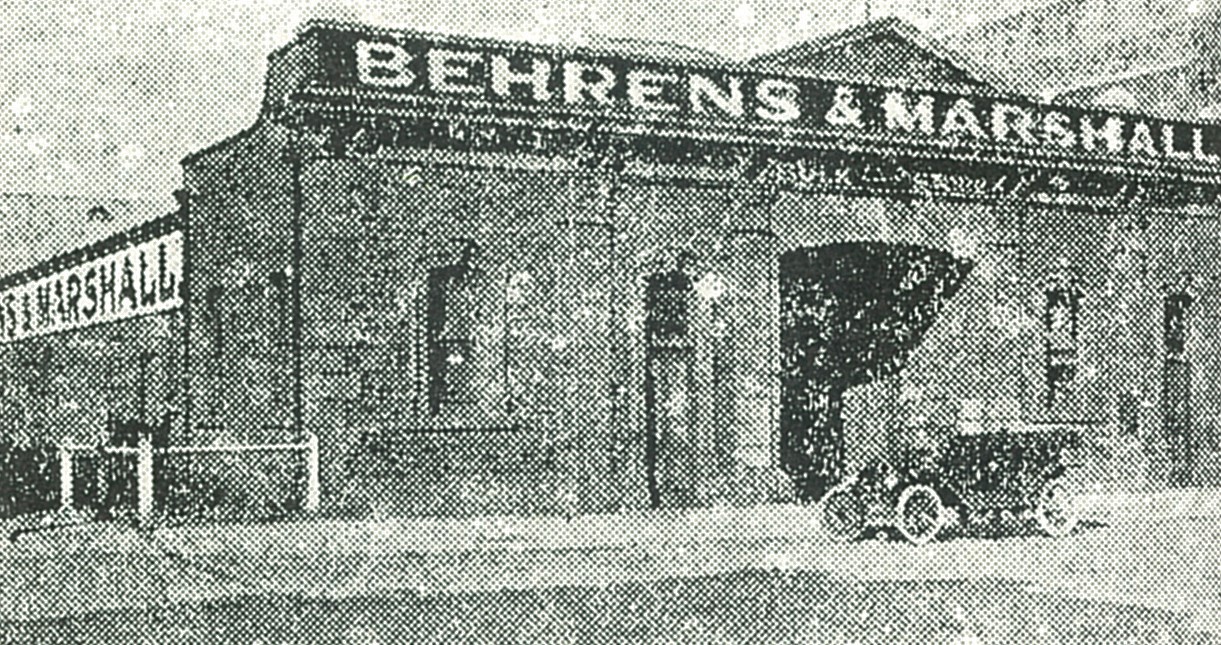

The expansion of Behrens & Marshall’s business to include the importing, display and selling of cars and trucks led in turn to the beginning of another aspect of the firm’s long history. The premises were seen to be inadequate for its growing operation and more space had to be found. This became a constant feature of the company’s history for many years to come.

When the partners commenced business in July 1912 as motor and general engineers they had obtained a sub-lease on premises at 150 Flinders Street, owned by the Collegiate School of St Peter and leased to the coachbuilders Thomas Barlow & Sons as showrooms. On 1 February 1912 James Archibald McGavisk became proprietor of Barlows, whose main premises were in Hindmarsh Square, and apparently McGavisk decided to vacate 150 Flinders Street soon after taking over the business. McGavisk lived in Queen Street Norwood, close to where Behrens lived with his parents, and this may have been how Behrens came to acquire the premises. At all events, the premises were sublet for a term of three years to Behrens & Marshall, who paid Barlows the sum of £8:13:4 per month in rent. On 3 August 1915 Behrens & Marshall took over the lease from the College in its own name. Late in 1921 Flinders Street was renumbered and the firm’s address was changed to 134 Flinders Street. The little iron building next to the Somerset Hotel which is on the corner of Flinders and Pulteney Streets was ideal for the firm’s original business. The floorspace was divided into a workshop and a garage, and the workshop was fitted up with the latest facilities for repairing motor cars and cycles, including two large drills. A newspaper reporter observed that neatness and cleanliness were features of the premises. However, there was hardly enough room to assemble and display the vehicles imported under the new agencies and more space had to be found. In June 1915 work was commenced to enlarge the Flinders Street property, and when the alterations were finished in August twice the number of cars could be accommodated. However, the storage and assembly of vehicles as large as the Sterling truck required even further space, and this was found nearby. The company’s ledger shows that, in addition to the rent paid to the College, from October 1917 a rental payment of ten shillings a month was made to Rogers Brothers. Rogers Brothers was a motor engineering firm which had commenced business at 249-251 Angas Street in August 1913 and at the end of 1915 had moved to a more spacious garage and workshop at 195-9 Flinders Street, at the time on the corner of Ackland Street which has since disappeared. In April 1918 The Mail printed an article on Behrens & Marshall, a ‘Progressive Firm’, and reported that after setting up in Flinders Street the firm had acquired the bulk store of the Continental Garage, which had been closed since the war. It is remembered that the Continental Garage was on or near the south-east corner of Flinders and Pulteney Streets, and perhaps this was the property to which Rogers Brothers moved at the end of 1915 and part of which they rented to Behrens & Marshall as a bulk store. Even then expansion continued to be the order of the day. Ten months after occupying part of Rogers’ premises Behrens told his employees that the premises were again being extended.

While the Enfield, Sterling and Enger agencies pushed the firm out into additional floorspace Behrens & Marshall retained its close association with the Ford car. From the beginning the firm had specialised in repairs and accessories for the Ford, and a Mail reporter on 20 April 1918 wrote words which the partners used as an advertising slogan when he said that there was not a part of this particular make which had baffled them. There were sound business reasons for the firm to relish such a reputation. Since its appearance in South Australia in 1909 the Model T Ford had taken the market by storm and the local distributors Duncan & Fraser did a thriving business. Both Johnnie Behrens and Ross Thiem had worked for Duncan & Fraser and had a thorough knowledge of the most popular car on the road. An agency for the Ford was out of the question since it was already pre-empted, so the firm expanded its business by handling other agencies while still backing up its claim to be a Ford specialist. Then for a while Behrens & Marshall became even more closely associated with Ford cars.

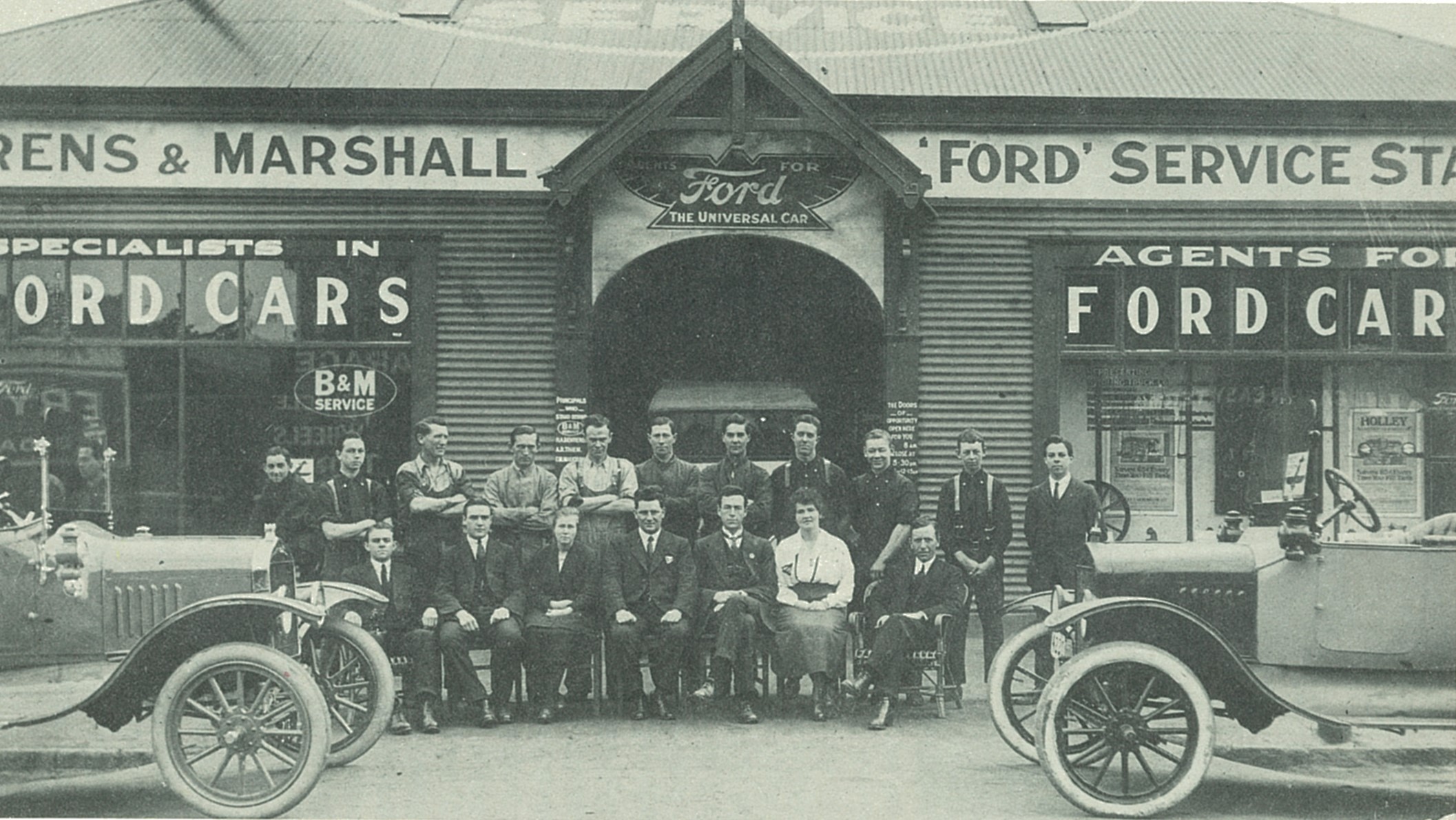

In 1918 Duncan & Fraser set new records in sales of the Model T Ford. In October that year fourteen new Fords were delivered in one day, 42 in one week, and 120 in one month. This was a record, not only for Duncan & Fraser, but also for South Australia. By that time Duncan & Fraser had decided on a new policy to handle the growing sales and demand. Early in May 1918 the press announced this new urban Ford policy. Duncan & Fraser had decided to utilise existing channels of marketing to promote Ford interests in the State. This was to be done by appointing what they called ‘limited urban dealers’, who would operate in specified districts near their own garages and thus be at hand to give service to Ford buyers in their districts. The choice for the first of these appointments was obvious. Newspapers reported that Behrens & Marshall, one of the most enterprising and businesslike motoring firms in Adelaide, specialised in repairs and accessories for the Ford and had always recognised the sterling qualities of that car. Duncan & Fraser had therefore appointed Behrens & Marshall as the first limited urban dealer, with the privilege of selling new Ford cars in the city and suburbs. Behrens & Marshall in turn made sure that the firm’s advertisements during the following months made the public aware of the benefits to be derived from this arrangement. The prospective buyer was assured that if he bought a Ford from Behrens & Marshall he was entitled to free specialist advice at the firm’s Ford Service Station. The very term ‘service station’, long before it came into popular currency, sounded progressive, and the promise apparently attracted customers. Press reports indicate that for some time Behrens & Marshall sold new Fords at the rate of ten to fifteen per month. By the time the firm changed its name to Maughan-Thiem Motor Company in December 1920 it was described as ‘essentially a Ford service and sales organisation.’ In July 1920 the firm gained press publicity for a special ‘sporting prince Ford’ which it built. The engine was specially made with aluminium pistons, leak-proof rings and light connecting rods. The coachwork, finished in royal blue with gold points, was done by J.S. Bagshaw & Sons Ltd, where Fred Maughan had served his apprenticeship, and the complete car weighed only 12 hundredweight. It was said to be capable of 50 miles per hour without any difficulty.

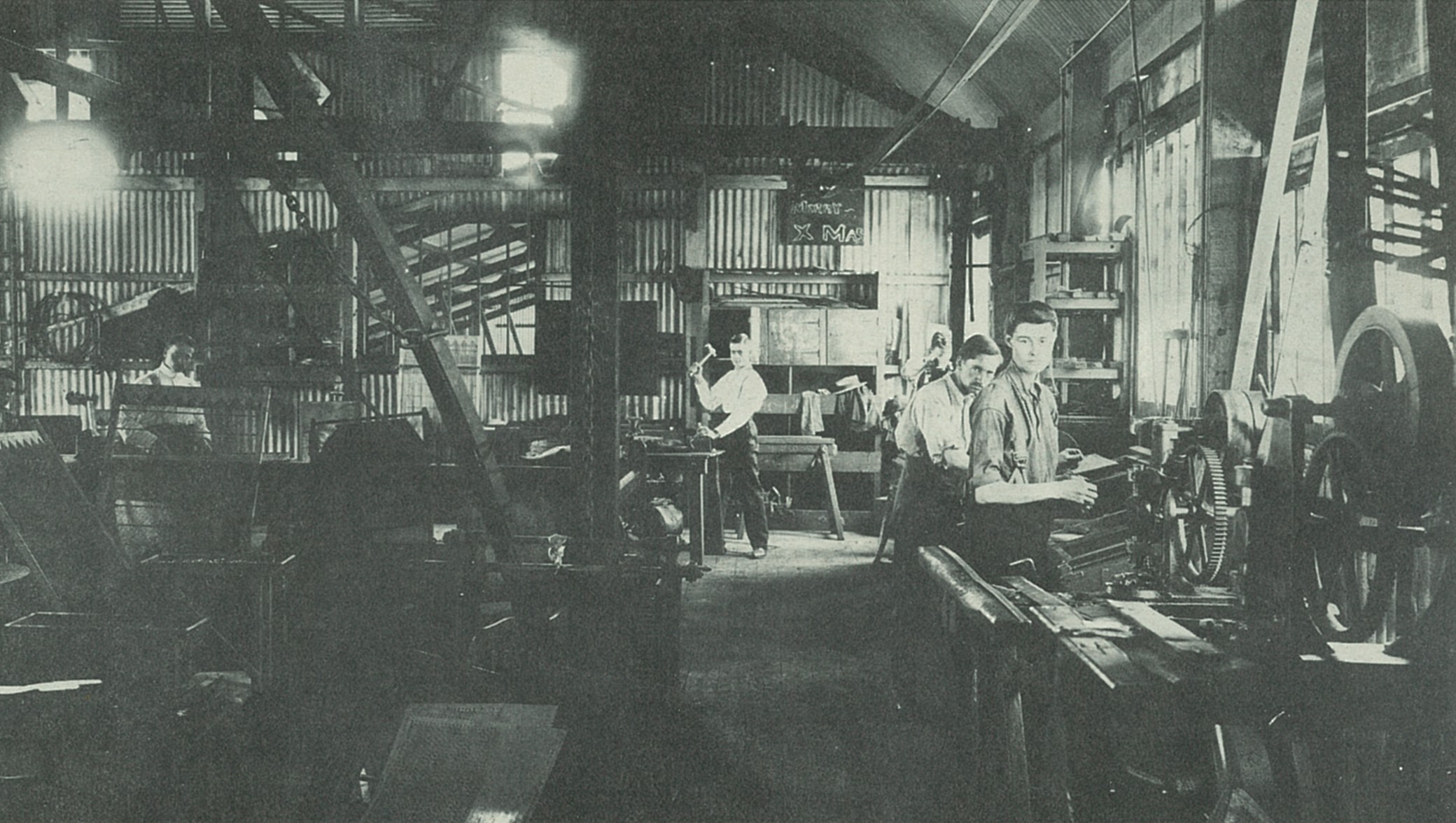

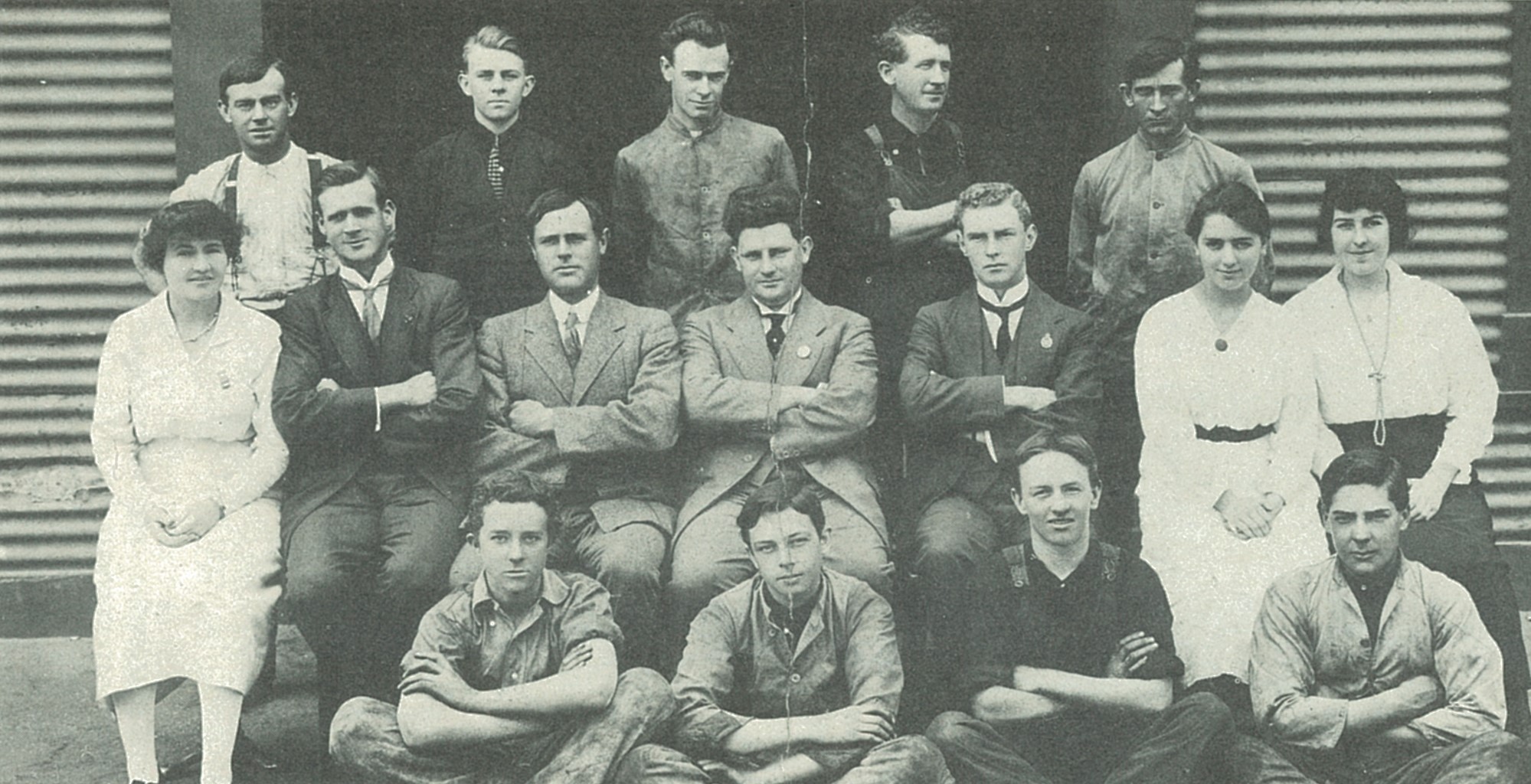

As the firm’s business grew so did its staff numbers. The firm commenced in 1912 with two employees who were gradually joined by others. Mr T. H. (Bert) Baldock remembers starting work there in 1914, when he was about fourteen years old. He applied to Behrens & Marshall because he knew two boys working there. He was interviewed by Johnnie Behrens, and the interview was apparently not very promising; two boys had just been put on and it seemed doubtful whether there was a vacancy. Nevertheless an envelope, embellished with the admonition ‘Run Postman Run’, carried the news that he had a job with the firm, where he started as head messenger boy. His first duty, he remembers, was to be introduced to a broom, and he had to keep the floors clean and pick up any nuts and bolts from the floor. Behrens apparently walked past one day and dropped two shillings. When Baldock pointed this out to him Behrens replied, ‘Yes, but what about all those washers and nuts and screws that you’ve missed on the floor. They’re worth more than two bob.’ Apart from learning such lessons in thrift and attention to detail Bert Baldock was required to run messages, such as buying the parts required for the firm’s motor repair work. En route he also bought the staff lunches and was rewarded with a cake or such by the girls in the office. One of the mechanics, Mark Welsh, was a keen fisherman, and Bert Baldock also bought his bait for him. This was a concoction known as ‘gentles’, consisting of maggots kept in bran. Of course, there was more serious work to do. The boys were apprentices and were introduced to the mysteries of the motor engine and the workings of the car in general.

By Christmas 1917 the staff numbered twelve, in addition to the four partners. Bert Baldock still remembers them. Mark Welsh was an engineer, originally from Broken Hill. The two cousins Alec Hersey and Fred Hersey were on the workshop staff. So too was Alf Pfitzner, nicknamed ‘Dirty Dick’ because he did some of the dirty jobs such as repairing Ford differentials; so too were Ken Johnson, who was nephew of Eric Marshall, and Clyde Close and Charlie Bradley and Les O’Connor. The office work was in the hands of Miss Henderson, Miss Sullivan and Miss Copeland. Marjorie Copeland remained with the firm for over forty years and was one of the longest-serving members of the staff. Others joined the staff shortly after Christmas 1917. W.R. Sommerville joined as a salesman in 1918. Mr Les Rasch became secretary; he was also organist at a church in Maylands which Miss Copeland attended. L.R. Rasch remained with the firm until the end of 1925 when he left to go into his own business, at first in partnership with George Mason and then on his own.

A series of newspaper cuttings held among the company papers makes it clear that from an early time the partners gave serious thought to relations between staff and management. For a time there was much publicity for various schemes of profit-sharing which, it was claimed, reduced friction between capital and labour and gave employees a proprietary interest in their firm, which in turn led to increased output and quality, obviated strikes and lockouts, and even increased the number of jobs available. By the beginning of 1918 Behrens & Marshall had decided to introduce a scheme of this sort into its business. The partners promised a bonus to the staff as a reward for quality workmanship. This was regarded as the payment to the employees of a dividend out of company profits and therefore as profit-sharing. To celebrate the distribution of bonus dividends the partners entertained the entire staff at a dinner at Bishop’s Cafe in King William Street, where the occasion was marked by speeches and entertainment. The first of these dinners was held 31 January 1918, and they became regular events. One of the bonus slips remains in the possession of the Maughan Thiem company. It is typed, signed by Behrens, and reads:

THE FIRST BONUS – and we trust that the one following will be greater. Are you interested?

The amount of the bonus varied according to the years of service. The bonus paid in August 1918 was equivalent to five shillings for each week of the previous month for senior employees and half that amount for juniors. In December 1918 the men received £2:8:6 each and again the boys received half that amount. Wages were not high, and these payments were a very welcome addition to the pay packet. They also created a measure of competition between the sections of the firm. Workshop staff, for example, insisted that spare parts used on a job should be credited to staff using them rather than automatically to the spare parts section. The monthly dinners accompanying the bonus distribution were abandoned for three months during the influenza epidemic of 1919, and the resumption of these occasions was marked by an excursion to Brighton in November 1919.

The partners tried to foster good relations between staff and management, not only by the distribution of bonuses at monthly dinners, but also by a series of lunch-hour talks. The talks lasted for half an hour and were usually on matters of practical interest to the staff. Mr Hugh Duncan of Duncan & Fraser, for example, spoke on ‘Tyres and their Repairing’, Mr C.W. Wittber spoke on dismantling the car engine and the care of tools, Mr Moody of the Savings Bank on the value of a Saving Bank account and Mr A. Ferguson spoke on the value of a technical education for men in the engineering business and exhorted the apprentices to devote their spare time to study. At the monthly dinner at the end of May 1918 Fred Maughan introduced the new superintendent of technical education, Dr Fenner, who then spoke to the staff about the advantages of profit-sharing and congratulated the firm on its progress. On the eve of his departure for his overseas trip Behrens said in a newspaper interview:

We thought it a good plan too, to adopt the principle of profit sharing and get together with our employes as much as possible. We like to think of our men working with us rather than for us. From our message boy upwards our staff can see us practically at any time of the day. Human nature should be properly studied, and then it will be found that if you give to the world the best you have the best wilI come back in return.

The advocates of scientific management would have applauded his statement; and the motoring editor of The Mail regarded the conditions it described as evidence that Behrens & Marshall was a progressive firm.

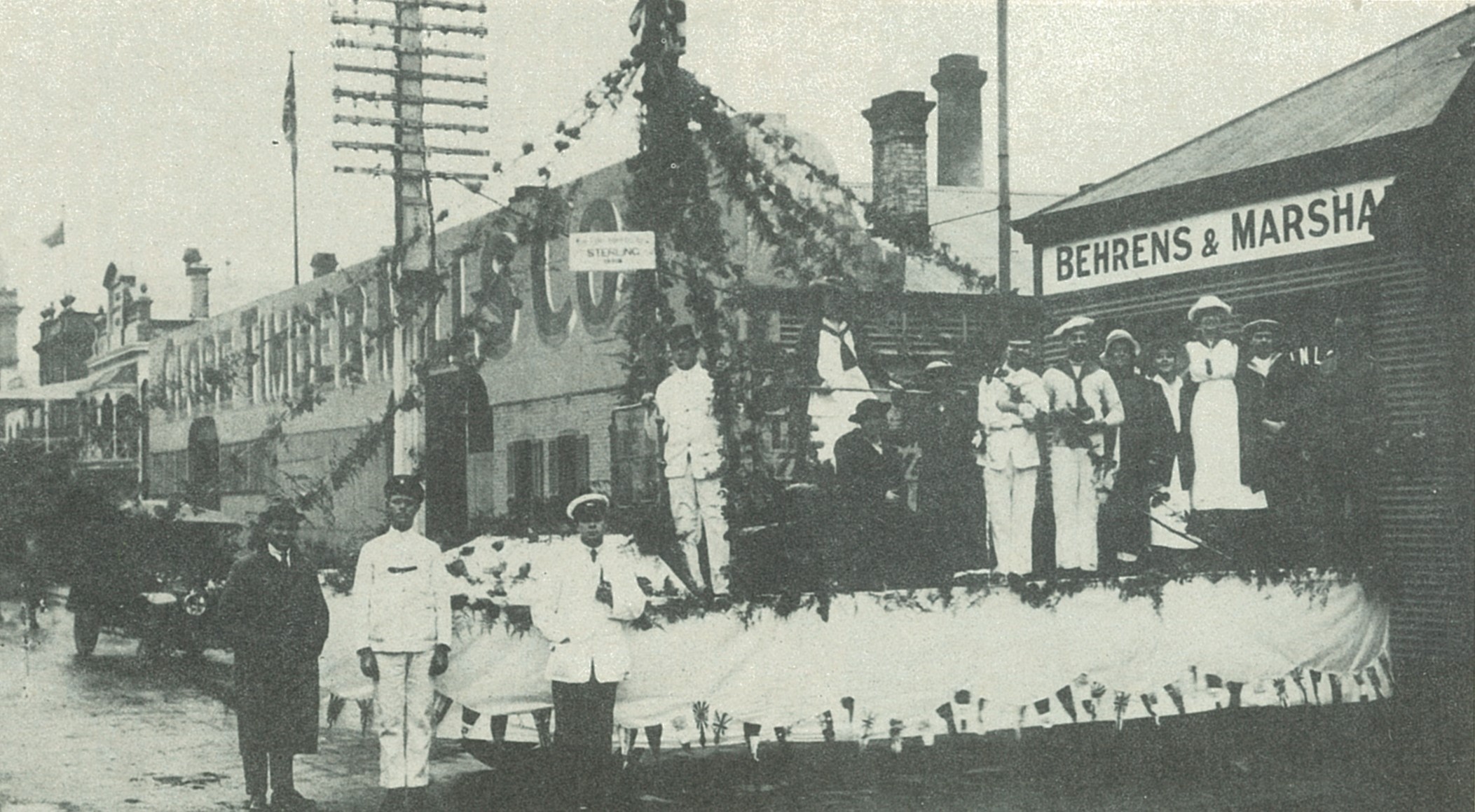

During the years of World War One the staff shared in a fund-raising effort for Red Cross. On Friday 28 July 1916 an Australia Day Procession was held in Adelaide to collect money for the Soldiers’ Fund to care for returned men. Eleven motor trading firms took part in the procession, including Behrens & Marshall. The firm, it is recalled, rigged up a Sterling truck to resemble a ship. Some of the employees were dressed as sailors and held out collecting baskets on the end of rods. Johnnie Behrens’ son, then a small child, took part in the event, and he remembers that his new white pullover became very dirty from diving under the seat to recover the odd coins which missed the baskets.

Needless to say, the staff was occasionally called on to use its skills in various ways. For example, in January 1915 it was reported that in addition to an exceedingly busy workshop Behrens & Marshall had the agency for the Goldfields Diamond Drilling Company of Melbourne and was engaged in boring for water in many suburbs around Adelaide. The firm had four power plants continually working at this, apparently with a good measure of success. In addition, the firm’s engineering skills were turned to the service of the Ford car in an original way. In March 1915 it was reported to have manufactured in its own works an armoured oil gauge designed for the Ford. By the time of the report a large number had been fitted and a good stock was in supply.

Behrens & Marshall was apparently the first Adelaide firm to install a kerbside Bowser petrol pump. In July 1917 Eyes & Crowle had asked permission from the Adelaide City Council to have one in front of its Pirie Street premises, but the Council had refused. Over two years later The South Australian Motor caustically commented that, although in Melbourne and Sydney nearly every garage had a Bowser pump on the kerb in front of its premises, the idea was too modern for Adelaide. The comment was obviously designed to influence the Adelaide City Council, for early in October 1919 that body had eventually given permission to Behrens & Marshall to install a Bowser on the edge of the footpath outside its premises. The Bowser, which first appeared in 1885, could supply petrol direct to the car tank at a rate of eight gallons a minute, and the risk taken by ‘a certain progressive firm’ in Flinders Street in experimenting with it was applauded by the editors of The South Australian Motor. The Mail noted that it was the first kerb pump installed in Adelaide. The City Council, however, obviously could not make up its mind about this innovation. Behrens & Marshall was given permission to let it remain in position for six months after it had been inspected by various officials, and motorists made full use of the pump which was available all day and night. By August 1920 the Council had decided that the pump must be removed and that no further pumps were to be installed; but two months later it reversed the decision and resolved to allow Bowser petrol pumps in certain thoroughfares for an annual rental of £10:10:0.